The RealReal is betting big on brick-and-mortar stores, a former touchstone of retail that COVID-19 weakened, as e-commerce becomes a go-to destination for consumers.

With permanent store closures rising countrywide, the digital native luxury goods consignor is expanding its physical retail footprint with new locations in Chicago and Palo Alto.

“What we find with our customers – they love consigning in the brick-and-mortar stores,” said Julie Wainwright, The RealReal’s CEO and founder, in a TV interview last month. “They love talking to experts, and they love to see and buy high-value things.”

While the company’s six physical stores bolster its supply of previously owned luxury items like Hermés handbags and Rolex watches, they increase losses for the still unprofitable San-Francisco-based consignor. And competitors threaten to outpace The RealReal by investing in data technology that optimize their e-commerce services, a sector of retail that younger, more tech savvy customers are flocking to.

COVID-19 accelerated the shift in the retail landscape from in-store shopping to online ordering, as customers were confined to their homes to stop the spread of coronavirus. Now, brick-and-mortars have a more “showroom effect” and serve as billboards, said Brian Nagel, equity analyst at Oppenheimer. “A lot of these retail stores are much more brand building,” he added.

The RealReal’s expansion is born out of the change in traditional retail as more than a point of sales. The company’s new location in Chicago on Michigan Avenue, which opened in early October, is a multi-floored, 12,000-square-foot consignment emporium that includes a watchmaker station and a dine-in café. And the 4,200-square-foot neighborhood store in Palo Alto that opened in late November helps The RealReal increase its supply of luxury consigned goods, the company told San Francisco Business Times.

On the surface, this is a bleak moment for The RealReal to invest deeper in its brick-and-mortar outposts. According to accounting firm BDO Global, 4,228 stores permanently closed in the first six months of the year, and over 50% of those closures came from major apparel retailers like Zara owner Inditex and H&M. But some retail analysts view this trend as correcting market saturation and not the sign of a dying industry.

“The traditional retailer was over-stored, and they’ve got to pull back,” said Jennifer Redding, equity analyst at Wedbush Securities. “That doesn’t mean that stores aren’t worth their value.”

Still, physical stores can exponentially add to a company’s expenses, said Kevin Mullaney, CEO of The Grayson Company, a retail consulting firm. Even if an e-commerce retailer sees a steady rise in revenue, often primarily from online orders in the current consumer market, the cost of running a brick-and-mortar store can overpower sales gains and drain profit margins.

The RealReal’s total operating expenses jumped 16% from $78.7 million in the second quarter of 2020 to $91.1 million in the third quarter, in large part because of the Chicago location. While the consignor does not disclose the costs of its stores, average retail rent in Chicago is $18.60 per square-foot per year, according to CBRE Group Inc., a commercial real estate and investment firm. That accounts for at least $223,000, which does not include utilities, payroll and other costs related to opening a store.

But analysts say investors are increasingly rewarding growth tactics, like a retail expansion, over immediate profits.

“If a company is profiting but limiting long term growth, that’s bad,” Nagel said. But the market still wants to see a “path toward sustained profitability,” he added.

The RealReal is showing signs of healthy growth. Although analysts estimate year end revenue to hit $309 million, a 2.8% year over year decline due largely to the pandemic shutdown in the second quarter, it is expected to rebound in 2021 at $420 million.

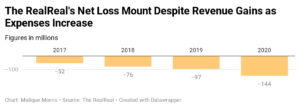

Yet the consignor, which debuted on the public market last June, is set to end the year with a deeper net loss of $144 million, versus last year’s 96.5 million. Analysts believe losses could shrink to $118 million in 2021.

Along with a precarious path to profitability, The RealReal is losing market value. The consignor’s market cap has dropped 21.6% from $1.62 billion at the end of 2019 to its current $1.27 billion valuation, as red ink fractured investor confidence.

While the pandemic has dealt the physical retail sector a hard blow, e-commerce giants in the luxury apparel sector are faring pretty well. Farfetch, a London-based multi-brand e-tailer, has seen a 419% increase in its market cap from last year. The company, which has a $20 billion valuation and does not operate any physical stores, is beefing up its online presence by partnering with China-based e-commerce behemoth Alibaba, an initiative that investors rewarded with a 12% boost in Farfetch’s share price following the news in early November. Conversely, The RealReal’s share price dropped 4% after the company announced its store opening in Chicago last month.

Marvin Fong, an equity analyst at BTIG, said e-commerce as a consumer platform for the secondhand luxury market is superior to physical retail, in an October note.

Wainwright, an e-commerce entrepreneur, founded The RealReal as an online consignment shop in 2011. The company gained popularity with high-end customers by branding itself as the premier digital marketplace for authentic secondhand luxury goods. After serving as CEO of the short-lived Pets.com, which shuttered during the 2000 dot-com bubble after nine months on the public market, Wainwright set out to build an online business that wouldn’t suffer the same fate.

Like its principal competitors ThredUp and Poshmark, The RealReal has capitalized on the rising eco-consciousness of Millennial and Gen Z consumers. And younger, more environmentally friendly fashion lovers are committed to buying online.

Mia Leff is an avid customer of The RealReal. The 20-year-old college student uses the site to build a sustainable wardrobe with pre-owned style staples from designers like Jil Sander and Rick Owens.

“I’m more willing to spend a larger sum of money for quality consigned clothing,” said Leff, who studies fashion communications.

Living in Denver, Colorado, prevents Leff from accessing The RealReal’s brick-and-mortar locations. But while she said she would pop into one of their physical stores to peruse if she had the chance, Leff is more likely to engage with the company on her phone. “I often use The RealReal’s app option to curate my dream wardrobe,” she said.

Pouring more money in cutting edge technology, like automation, to better serve digitally savvy customers like Leff can strengthen a company’s long-term financial health by lowering costs, said Andre Artacho, managing director of Two Nil, a growth consultancy firm.

To date, The RealReal has spent 8% more on technology year over year, according to its third quarter earnings release, but Matt Gutske, the company’s chief financial officer, during last month’s investor call said automation can be a bigger priority.

Beyond optimizing the customer experience and cutting expenses, Artacho said more robust automation can streamline the way an e-commerce retailer operates. “It’s not just about reducing cost, but about the efficiency of the company as a whole,” he said.